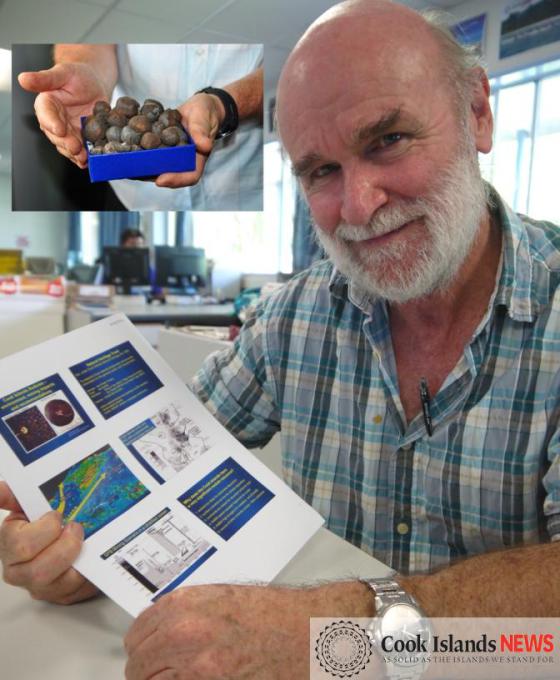

Gerald McCormack, Director of the Natural Heritage Trust. The Cook Islands’ exclusive economic zone contains 10 billion tonnes of manganese nodules like those inset, according to a geological assessment.

Source: Cook Islands News

Environmental factors from any potential seabed mining activities in the Cook Islands were the focus of a presentation held at the University of the South Pacific last night.

Gerald McCormack, Director of the Natural Heritage Trust, delivered his talk titled “Cook Islands nodules: Some environmental considerations”, which included a visual presentation on seabed geography, possible mining methods, potential effects on marine life, and recommendations.

With the environment his primary concern, McCormack said he wanted to focus specifically on the Cook Islands and its own unique ocean ecosystem – as opposed to other potential seabed mining locations such as New Zealand or Papua New Guinea, which he says bear few similarities to the nation’s situation.

While conducting research, he said he concentrated on the South Penrhyn Basin – an area he describes as “ ... the most dense area of nodules in the world” - located north of Aitutaki, east of Suwarrow, and south of Penrhyn.

Assuming an annual harvest of one million dry tonnes per year – enough nodules to cover an area the size of the surface of Rarotonga – McCormack said one particular area within the South Penrhyn Basin contains enough material to keep miners busy for at least 100 years.

The next densest area in the zone has enough nodules for a further 80 years of mining.

“I really want people to understand how massive this operation is,” he said.

McCormack said the nodules are resting on the ocean flooring, which would remove the requirement to dig.

Despite their convenient location, he is convinced that mining activity would harm, even kill, all the animals that live in the cold, dark confines of the ocean floor – a desolate landscape five kilometres below the water’s surface.

‘Benthic Macrofauna’ is the term used to describe some of the animals found at those depths. They consist of roughly nine different species and range in size from 0.3 mm to 4 cm long. McCormack said it is likely these animals will get run over or sucked up by mining machinery.

Apart from these creatures, a lack of nutrients creates an undersea environment that contains little life, he said. He quotes a German study which described the zone as “impoverished”, “not very diverse”, and with a low density of animals.

“There is very little biodiversity down there,” he said. “Nevertheless, we should preserve it.”

Also of concern are possible effects on the country’s migratory whales.

McCormack said steps need to be taken to ensure sound from mining activities will not interfere with whales and their unique communication systems.

To protect the South Penrhyn Basin’s marine life, he proposes the adoption of an “ecosystem approach”, which entails the establishment of a biodiversity protection area (BPA) prior to the commencement of any mining.

McCormack said the protective area should be located “upstream” from mining activities, and kept “pristine”.

The establishment of such a zone would require further data on the direction and speed of the ocean current at the depth of the sea floor, and a survey of marine life would need to be taken by any company licensed to undertake mining activities.

The purpose of the BPA would be to have a prototype area, with hopes that the mined regions could revert to how they appeared prior to the harvesting of any nodules – and without any reduction in biodiversity.

Also prior to the beginning of mining, McCormack said stakeholders should agree to a set of practices and methods, such as the “Sustainable Seabed Mining” guidelines established by England’s University of Southampton.

Seabed mining should be a “totally ecologically clean operation,” said McCormack.

“My presentation is to show Cook Islanders how this can be done properly.”

- Elizabeth1's blog

- Log in to post comments