Marape has failed to tackle chronic corruption

Ten months after taking power the government of James Marape has completely failed to deliver on its promises to tackle Papua New Guinea’s chronic corruption.

James Marape was elected as Prime Minister on the back of a growing wave of discontent over political corruption and the misuse of public funds and the initial signs from the new government were promising.

The Public Accounts Committee emerged from the shadows to hold televised hearings into the procurement of medicines and medical supplies in the Department of Health and Secretary Kase was quietly removed. A high-powered Commission of Inquiry was appointed to investigate the disastrous UBS loan scandal. Vocal corruption critic Bryan Kramer was appointed Minister of Police and ex-Task Force Sweep boss Sam Koim took command at the Internal Revenue Commission. Meanwhile, the legislation to establish an Independent Commission Against Corruption was dusted off and brought back to Parliament.

But the initial wave of optimism that the Marape government would decisively tackle the chronic corruption that is undermining service delivery and impoverishing the nation has been dashed in the face of overwhelming evidence that in Papua New Guinea it is business as usual.

Government Minister William Duma, who managed to walk away from the Manumanu land scandal without facing any charges despite the weight of the evidence, seems just as immune from any sanction over the Horizon Oil scandal. While the Australian Chief Executive of the oil company has been terminated after the Board described his position as ‘untenable’, Duma has not even been made to step aside while Australian and local police investigate.

Meanwhile 38 of 40 Maserati’s which sell for around $140,000 each in Australia are still sitting idle in a warehouse in Port Moresby. Yet the Minister responsible for the purchase, Justin Tkatchenko, who falsely claimed firstly that the cars were being imported at no cost to PNG and then were ‘selling like hot cakes’ has not answered for misleading statements or the waste of upwards of K20 million. To make matters worse, while some APEC vehicles are sitting idle the government is again spending millions on hire cars to help with the COVID-19 response.

Nowhere is the lack of accountability more apparent than at the very heart of the Prime Minister’s own Department. In February the Chief Secretary Issac Lupari had his contract extended, at least temporarily, despite the numerous allegations against him and the specific promises Marape made to Parliament last year that the position would be advertised and a new appointment made. Lupari has never answered for the historical allegation contained in the Department of Finance Commission of Inquiry report that he defrauded the State and the nation is still waiting to see the long-awaited audit APEC expenditure in which he played a central role.

The announcement in March that the controversial Paga Hill Estate has been granted tax concessions as a Special Economic Zone is another example of a government committed to business as usual. Despite the evidence of questionable land deals, political beneficiaries, human rights abuses and the previous record of the project CEO, the government has endorsed the project and all its grandiose claims without any proper economic analysis or public consultation.

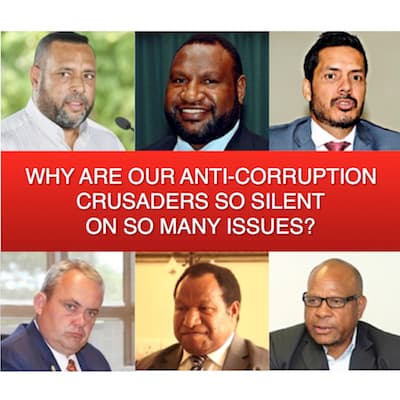

Not only does the government seem committed to business as usual, it is very worrying that the previously vocal anti-corporation advocates among our MPs are so silent on all these issues.

Meanwhile the Ombudsman Commission which is tasked with policing the Leadership Code seems to have fallen into a terminal sleep.

While some may point to the current COVID-19 crisis and State of Emergency as having stalled progress on the ICAC and the UBS COI, the truth is things were moving at a glacially slow speed even before the pandemic. The COI has faced numerous delays over funding and issuing visas and the government was showing no inclination to get the ICAC legislation fast-tracked through Parliament and a new institution set up.

In the last 10 months, despite a smattering of arrests and charges, there has not been one prosecution of a high-profile leader for corruption or misappropriation and not one Minister forced to resign or even temporarily step-aside.

The sight of the government now conducting its own ‘internal audit’ of spending under the State of Emergency despite the serious documented allegations against the Minister of Health only emphasises how far the Marape government has failed to deliver on its promises.