Source: Scott Waide, My Land, My Country

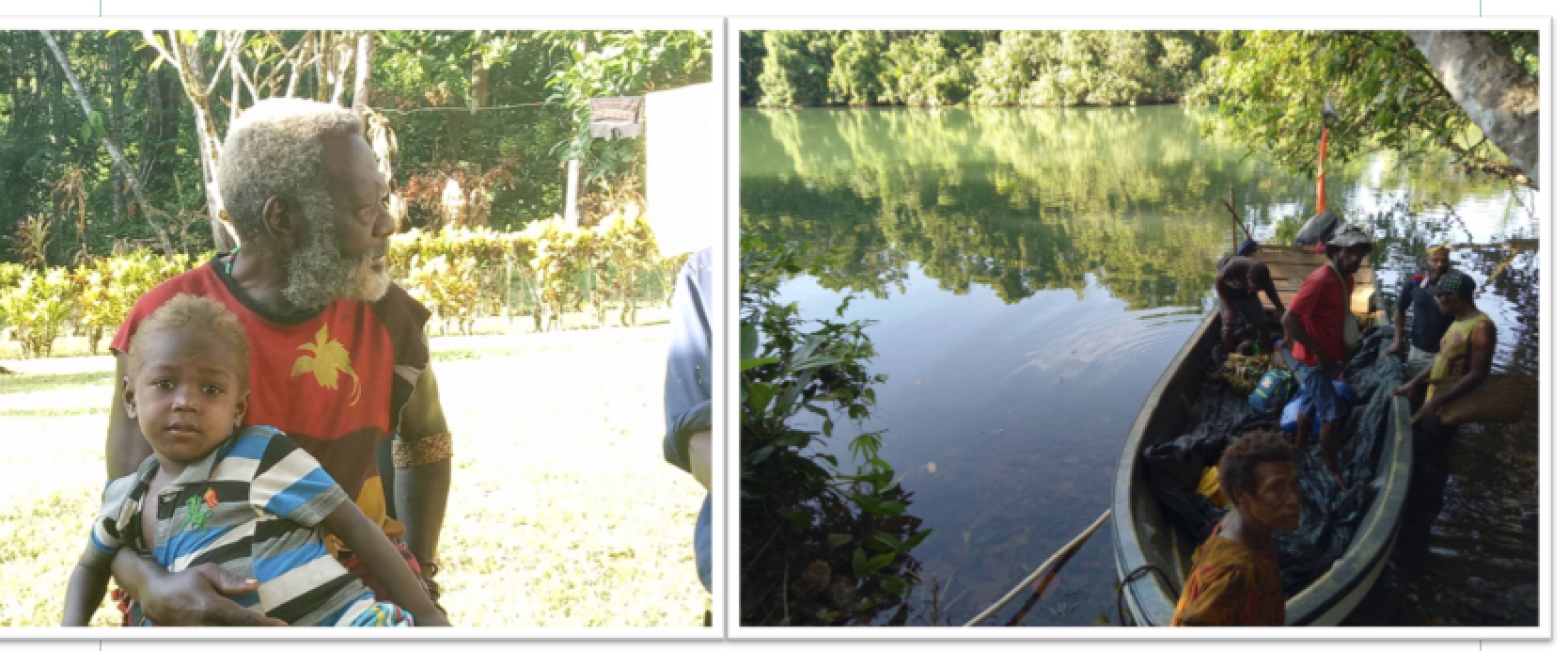

Chief William Ape Hawa is a straight shooter and a wise old fella who presents me with a shell necklace used as the local currency during important ceremonies. He apologizes for not giving me the gift the day before when I arrived at his Tavolo village on the border of East and West New Britain.

“When new visitors come,” he says in Tok Pisin, “We give them a ‘tanget’ headdress. That tells you that you shouldn’t be afraid or shy. It means you are welcome.

“Then before you go, we give you the necklace which means, “go in peace.”

Chief William speaks with a lot of wisdom and understanding spiced with wicked, truthful humor. He talks a bit about life and marriage of the young and then our conversation leads on to the Special Agriculture Business Leases (SABL) issued by the Government.

Tavolo is in the Melkoi LLG area of Pomio District, East New Britain. For the people here, the term Special Agriculture Business Lease triggers a lot of anger.

“What kind of laws do we have?” says Chief William. “They tell us that our land is part of a SABL and we had no part in that decision!”

Like many other SABL areas, other people signed on their behalf.

The Tavolo people who number about 600 own 18 thousand hectares of land. They have no intention of giving up the pristine rainforest over to the Malaysian company that intends to log their land and plant oil palm.

But Chief William and his people are under immense pressure to surrender their land.

There is oil palm development in neighbouring West New Britain. In the next local level government area which includes the district headquarters of Palmalmal, large areas of customary land have been logged out. Landownership is now being disputed in court. Much of trouble has come about because of agreements that were hastily signed.

Over the past 20 years, the people of Tavolo developed a conservation area over the 18 thousand hectares of land. The government recognised this. The decision has come with its benefits. Fish numbers have been replenished, bird species have become more visible and food is plentiful.

But now they are battling a decision that overrides theirs to keep their conservation area.

“They wanted to build a road into our land and we said: NO,” says Peter Kikeleng, the Ward Councillor who only found about the oil palm development plan for his land during an LLG council meeting at Palmalmal.

“There was only one copy of the document being passed around. When it came to me, I picked it up and walked out of the room. I said ‘this development is on my land and how come I don’t know about it?’”

This has been a steep learning curve for the community. They now have to raise K10,000 to pay for a lawyer to represent them in court. As far as they are concerned, nobody wants to know about their plight and the government doesn’t care.

This court case is just one of the many different land related cases initiated by different parties for different portions of land.

In Pomio, the promise of money and power it is tearing families apart.

One man told me, the landowner company took out a restraining order against him because he “tried to stop the oil palm development.”

In Tavolo, the Ward Councillor’s cousins have him listed as a defendant. He says outside of court, they are still family.

But when the court case is over, how much damage will have been done to the communities who have to contend with a 99-year lease agreement forced upon them.

- ACTNOW's blog

- Log in to post comments