Seabed Mining: An Invisible Land Grab

By Sylvia Earle, National Geographic

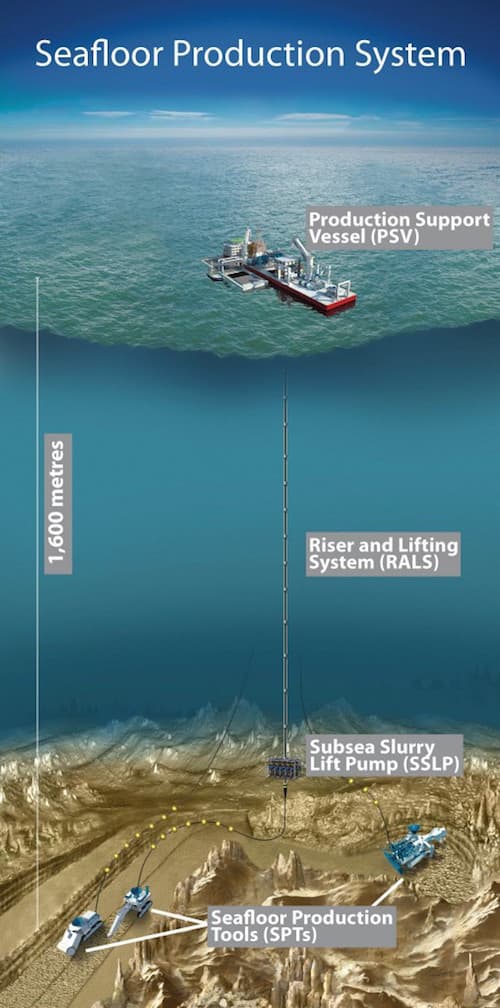

Thousands of meters beneath the azure ocean waters in places like the South Pacific, down through a water column saturated with life and to the ocean floor carpeted in undiscovered ecosystems, machines the size of small buildings are poised to begin a campaign of wholesale destruction. I wish this assessment was hyperbole, but it is the reality we find ourselves in today.

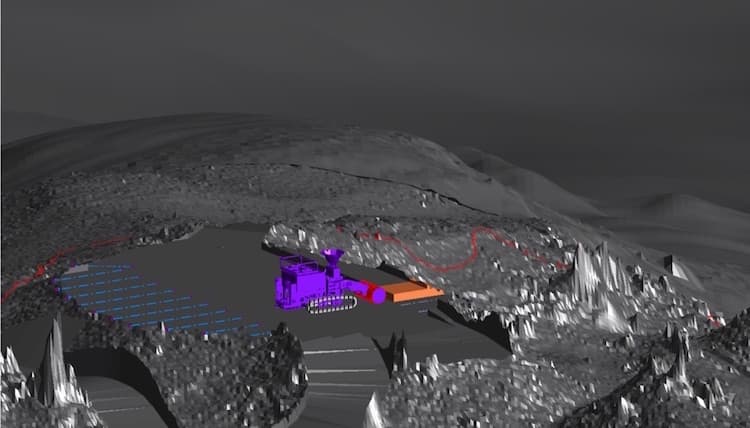

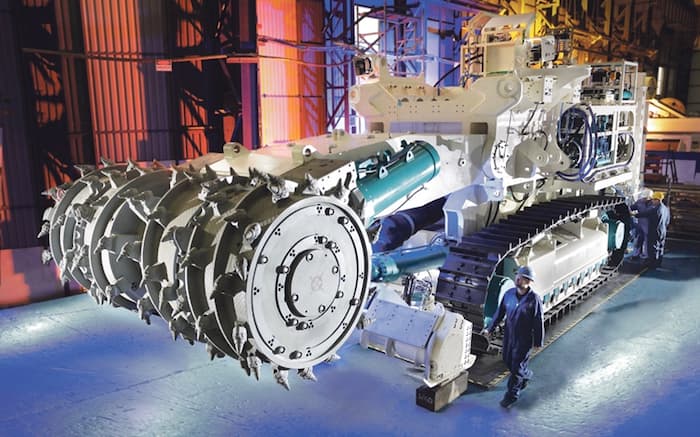

A deep sea mining machine

After decades of being on the back burner owing to costs far outweighing benefits, deep sea mining is now emerging as a serious threat to the stability of ocean systems and processes that have yet to be understood well enough to sanction in good conscience their large-scale destruction.

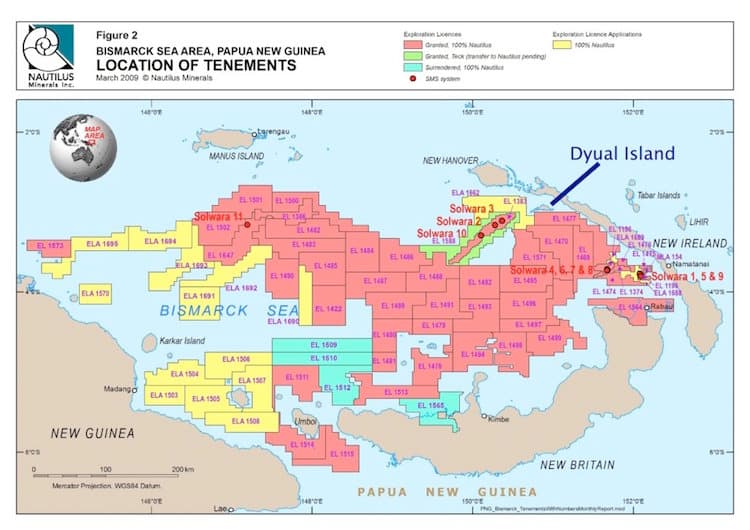

Critical to evaluating what is at stake are technologies needed to access the deep sea. The mining company, Nautilus Minerals, has invested heavily in mining machinery. However, resources needed for independent scientific assessment at those depths are essentially non-existent.

SIGN THE PETITION: Stop experimental seabed mining in the Pacific

The layout of a mining operation

China is investing heavily in submersibles, manned and robotic, that are able to at least provide superficial documentation of what is in the deep ocean. Imagine aliens with an appetite for minerals flying low over New York City taking photographs and occasional samples and using them to evaluate the relative importance of the streets and buildings with no capacity to understand (or interest) in the importance of Wall Street, the New York Times, Lincoln Center, Columbia University or even the role of taxi cabs and traffic signals. They might even wonder whether or not those little two-legged things running around would be useful for something.

The International Seabed Authority, located in Jamaica and created under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is currently issuing permits for mining exploration. At the very least, might there be ways to issue something like “restraining orders” owing to the lack of proof that no harm will be done to systems critical to human needs? Or also at the very least protecting very (very, very) large areas where no mining will be allowed?

The role of life in the deep sea relating to the carbon cycle is vaguely understood, and the influence of the microbial systems (only recently discovered) and the diverse ecosystems in the water column and sea bed have yet to be thoughtfully analyzed. If a doctor could only see the skin of a patient, or sample what is underneath with tiny probes, how could internal functions be understood?

The rationale for exploiting minerals in the deep sea is based on their perceived current monetary value. The living systems that will be destroyed are perceived to have no monetary value. Will decisions about use of the natural world continue to be based on the financial advantage for a small number of people despite risks to systems that underpin planetary stability – systems that support human survival?

In the 1980s, when deep sea mining first became a hot topic, it seemed preposterous to think that humans could up-end planetary processes by burning fossil fuels, clear-cutting forests and oceans, producing exotic chemicals and materials and otherwise transforming – “taming” – the distillation of all preceding earth history for our immediate use.

A tragedy of the commons for the benefit of the few

Buried within the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act of 1980, US legislation sponsored by Senator Lowell Weicker about deep sea mining, there is a provision that mandates for US interests to establish “Stable Reference Zones” of equal size and quality to those proposed for exploitation. The wording in this law was taken from a resolution crafted at the IUCN meeting in Ashkabad in 1978 that I helped draft and later took to Senator Weicker’s trusted scientific advisor, Robert Wicklund, for consideration.

The IUCN World Conservation Congress occurring this September in Hawaii provides a ripe opportunity to set in motion some significant and very timely actions that could help blunt the sharp edge of enthusiasm for carving up the deep ocean. Whatever it takes, there must be ways to elevate recognition of the critical importance of intact natural systems.

The environmental destruction caused by open mining on land is well documented

We need technologies to access the deep sea to independently explore and understand the nature of Earth’s largest living system. But most importantly, we need the will to challenge and change the attitudes, traditions and policies about the natural world that have driven us to burn through the assets as if there is no tomorrow.

This “as if” can be a reality – or not – depending on what we do now. Or what we fail to do. However, there is undeniably cause for hope: there is still time to choose.

National Geographic Society Explorer in Residence Dr. Sylvia A. Earle, called Her Deepness by the New Yorker and the New York Times, Living Legend by the Library of Congress, and first Hero for the Planet by Time Magazine, is an oceanographer, explorer, author and lecturer with experience as a field research scientist, government official, and director for corporate and non-profit organizations including the Kerr McGee Corporation, Dresser Industries, Oryx Energy, the Aspen Institute, the Conservation Fund, American Rivers, Mote Marine Laboratory, Duke University Marine Laboratory, Rutgers Institute for Marine Science, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, National Marine Sanctuary Foundation, and Ocean Futures.

Formerly Chief Scientist of NOAA, Dr. Earle is the Founder of Deep Ocean Exploration and Research, Inc. (DOER), Founder of the Sylvia Earle Alliance (S.E.A.) / Mission Blue, Chair of the Advisory Council of the Harte Research Institute, inspiration for the Ocean in Google Earth, leader of the NGS Sustainable Seas Expeditions, and the subject of the 2014 Netflix film, Mission Blue. She has a B.S. degree from Florida State University, M.S. and PhD. from Duke University, 27 honorary degrees and has authored more than 200 scientific, technical and popular publications including 13 books (most recently Blue Hope in 2014), lectured in more than 90 countries, and appeared in hundreds of radio and television productions.