Papua New Guinea's real economy

Corporations fill the media with talk about large-scale industries, resource extraction and export earnings. However, Papua New Guinea’s real, rural based, mainstream economy is far bigger and deserves much greater attention.

Effrey Dademo and Tim Anderson

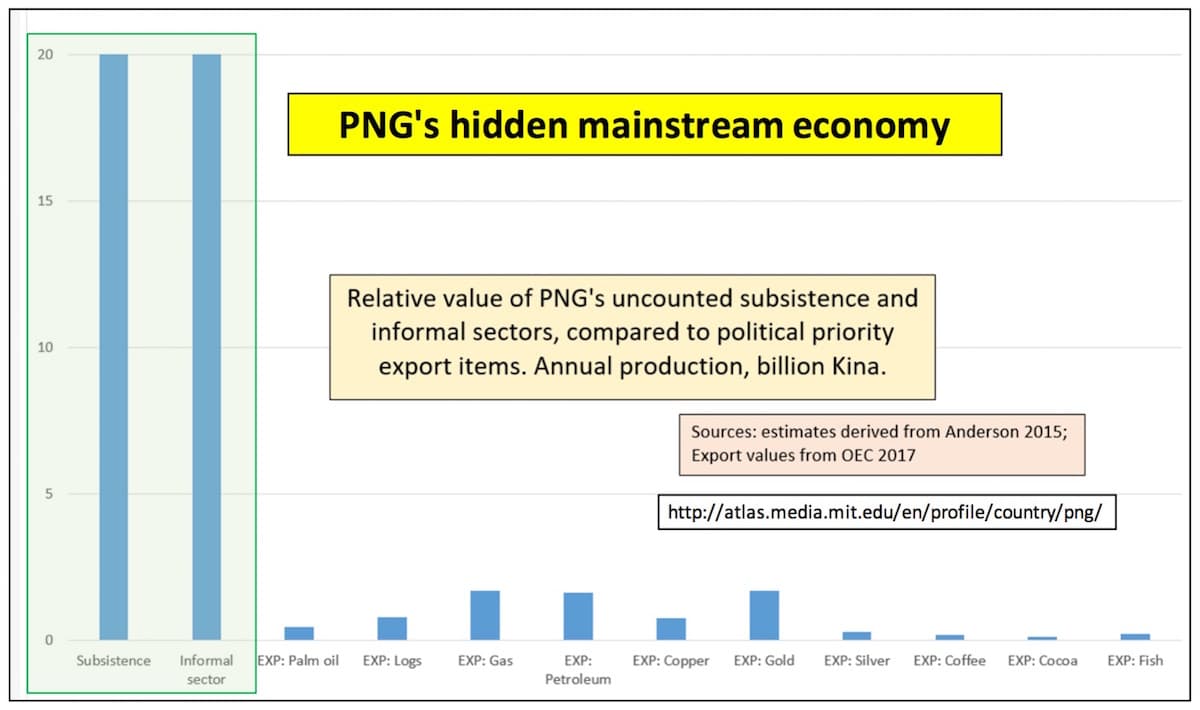

Economic discussion in PNG often focuses on natural gas, mining, logging, tuna and large-scale agriculture such as oil palm. If we believe the media, these are the things that matter and they drive our economy.

However, these export orientated industries are tiny when compared to PNG’s real mainstream economy, small farming.

Small farming? Small Kina you say? Not so!

Studies into rural livelihoods over the past decade show that customary land is highly productive, but its output and impact is neither measured properly nor publicly recognised.

That affects how we see family income but also national income. It also impacts our government’s decision making, our whole education system and how we view development.

If a rural family had to buy at regional markets what comes from their gardens, they would have to spend up to 20,000 Kina per year. That gives us an idea of the real value of subsistence output (what we produce to feed ourselves). The value of domestic informal or market trading, including garden produce, is almost the same again, another K20,000 a year.

One million rural families could therefore be producing K40 billion in real value per year. That dwarves the annual combined output of gold (1.7bn), gas (1.69bn), petroleum (1.63bn), copper (0.75bn), logging (0.8bn) and palm oil (0.47bn) which totals just K7 billion.

That $40 billion value should be borne in mind when considering other economic activities that destroy or displace customary production, such as logging, oil palm or industrial sites. We need to be much more mindful of what we stand to lose in deciding whether change is justified or necessary.

We should also be mindful of the employment that this real mainstream economy provides. Over 1 million people in PNG work in their gardens everyday producing food and cash crops that nurture and sustain their families and communities.

Many economic surveys, especially those commissioned by banks, only measure ‘formal’ commerce as this is what suits their interests. They ignore subsistence production and housing and often also bypass informal trading. When these are combined with small business, export crop and employment, rural family output can easily reach an equivalent value of 30,000 or 40,000 Kina per year.

When customary land is taken from families or clans there is a massive economic loss to those people and the nation. There may also be losses in social value (reserve employment, food security and cultural value) and in ecological goods and services.

ACT NOW! has recently commissioned the development of a framework for assessing compensation for those who have lost land due to illegal SABL leases. In that framework all these factors must be taken into account and what we find is that the losses are quite staggering.

If we are to understand the real meaning of development and build a better future for all Papua New Guinean’s we need to start by recognising and then building and strengthening our real mainstream economy.