DSTP proposed for the Huon Gulf is problematic

White, sandy beach at Busamang village in Salamaua LLG area, a natural property of the peoples that can be utilized for ecotourism business.

By Wakang Awasa Luthou / For and on behalf of the coastal stakeholders of Wafi-Golpu mine

The State has already approved in principal the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for Wafi-Golpu Mine (WGM) in Morobe Province and issued a 50-year Environmental Permit (EP) for operations to begin soon.

However, for the Deep Sea Tailings Placement (DSTP) proposed for the Huon Gulf, the land and sea owners within 30km radius of the DSTP are adamant that the DSTP will be a disaster to their sustenance, livelihoods and environments. Despite the WGM environmental team frequenting coastal villages within 30km radius of the DSTP to preach the deception that there will be NO ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF THE DSTP on their sustenance, livelihoods and marine environments, the people are still not convinced one bit.

Despite the James Marape Government’s agenda of Taking Back PNG, the manner in which the EIS for WGM has been approved along with the issuance of an EP is a total contradiction to the Take Back PNG agenda. The way policy processes and legislative precepts have been hijacked in the name of economic development from the WGM operations shows that PNG is yet to be taken back from Papua New Guineans themselves.

This article is a brief review of the EIS for WGM, especially the process used in approving the EIS and the issuance of a 50-year EP to WGM and issues in regards to the DSTP proposed to be constructed in the Huon Gulf. The objective of this article is to make the public and the state aware of the social, economic and environmental consequences of CEPA recklessly approving an EIS and issuing an EP to a mining company without giving due diligence to the contents of such a document and the concerns raised by stakeholders.

The article reveals a raft of fundamental flaws in the EIS process, including

- No proper stakeholder consultation

- No baseline studies for coastal people

- No free prior informed consent

- Misleading bathymetry data

- Threat to protected turtles

- Threat to local deep-sea fisheries

- Carbon capture impacts

- Incomplete data on fisheries

- Threat to mangrove swamps

- Incomplete data on biodiversity

Conclusions are drawn in regard to the issues discussed herein and recommendations are given to rectify the status quo with the EIS for WGM in regard to coastal stakeholders and their environments.

Stakeholder Consultations

Prior to approval of the EIS and issuance of the EP, several stakeholder consultations were held by CEPA for the public to comment and submit their views on the EIS for WGM. The objectives of these stakeholder consultations were to: (1) obtain views of the public on the EIS for WGM; (2) for the public to make verbal presentations and written submissions to CEPA for their perusal; and (3) for CEPA to make recommendations on gaps and issues identified by stakeholders in the EIS to WGM to make appropriate changes and additions to the document before a final version is released.

In these stakeholder consultations, many stakeholders made verbal presentations and submitted their views in writing to CEPA for their perusal. People representing coastal communities of the Huon Gulf that are to be affected by the DSTP also made verbal presentations and written submissions to CEPA on behalf of their peoples.

However, the stakeholder consultations were nothing more than a formality for CEPA to tick boxes in the whole process of approving an EIS in principal and issuing an EP to WGM. The submissions made by stakeholders to CEPA were not taken on board by CEPA and the developer before the EIS was approved in principal and an EP was issued to WGM. Although there is provision within the Environment Act 2000 for the Director of CEPA to ask the developer to take on board stakeholder views and make appropriate changes and additions to the EIS before it is approved in principal and an EP is issued, this was not the case for WGM.

Therefore, it was a waste of time for stakeholders to make verbal presentations and written submissions to CEPA for their perusal. Moreover, government funds, time and other resources were wasted on stakeholder consultations when they amounted to nothing more than a formal process for CEPA to tick boxes for approval of an EIS and issuance of an EP for WGM.

Baseline Studies for Coastal Peoples and their Marine Environments

Studies done by WGM consultants on the near and offshore marine environments of the Huon Gulf, within the 30km radius of the proposed DSTP, raises a lot of questions on the integrity of the EIS approved by CEPA and the EP issued to WGM.

The social, economic and environmental baselines for coastal peoples living within 30km radius of the DSTP have not been adequately captured in the EIS for WGM. The coastal peoples living within 30km radius of the DSTP in the Huon Gulf will be the ones dangling at the end of the chain of activities and impacts of the WGM and will be the ones to be severely and immediately impacted for 5 or more generations as the WGM will supposedly last more than 100 years.

With lack of baseline data for coastal peoples living within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP, the State and the developer are treating coastal stakeholders as second class citizens, and their sustenance, livelihoods and environments seem to be of no consequence as far as the development of WGM is concern.

A baseline study is necessary for any type of natural resource development, and the development of WGM is no exception. Therefore, the EIS for WGM must include data for SML landowners, pipeline landowners and DSTP land and sea owners. But at the moment, the EIS for WGM is lacking baseline data for coastal peoples within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP.

Having a proper baseline data for coastal peoples living within 30km radius of the DSTP in the EIS for WGM will ensure proper compensation payments for the loss of their sustenance, livelihoods and environments as a result of any mishap from the proposed DSTP. A proper baseline data will ensure coastal peoples are compensated based on the intrinsic values of their sustenance, livelihoods and environments, and not based on some face value.

Natural Property and Free, Prior and Informed Consent

According to the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) under the United Nations covenants on Human Rights, indigenous peoples have rights to their natural properties such as the sea and beaches, coral reefs, mangrove swamps, seagrass meadows, seaweed, fish stocks and others. But before natural resources are developed or a development activity will have some impact on the natural properties of the indigenous peoples, the principle of FPIC must be sought.

WGM staff travelled the coastal villages of the Salamaua, Wampar, Ahi and Labuta LLG areas with the message that a DSTP will be located off the shoreline of Wagang village in Ahi LLG area for disposal of mine tailings. Moreover, the people were informed that the DSTP would not have any impact on the marine environment.

However, the way information on the DSTP was disseminated to coastal peoples of Salamaua, Wampar, Ahi and Labuta LLG areas by WGM staff was never in line with the principle of FPIC. People were never given adequate information to which they could digest, make informed decisions based on the information disseminated and give their consent to WGM to dispose of its mine tailings into the Huon Gulf.

The coastal peoples were simply told that the DSTP would not have any impact on their sustenance, livelihoods and environments. Then all of a sudden the EIS for WGM was approved in principal and an EP was issued for the company to begin operations, which would include the construction of a DSTP off the coastline of Wagang village in Ahi LLG.

The coastal peoples of Salamaua, Wampar, Ahi and Labuta LLG areas will now have to live with a DSTP that they never gave their consent to in the first place. The peoples have been coerced into accepting a DSTP through the approval in principal of an EIS and the issuance of an EP by CEPA to WGM to begin operations.

Therefore, the principle of FPIC was never used to obtain the peoples consent for a DSTP to be constructed in the Huon Gulf, which is a breach of the indigenous peoples’ human rights.

Bathymetry of the DSTP Fallout area

The EIS for WGM states that descending mine tailings will be driven downslope by its higher density against a column of water at 200m below sea level, and due to its higher density the tailings will settle at the bottom of the sea and will be negatively buoyant.

However, bathymetry of the Huon Gulf shows that the area proposed for the DSTP fallout is too shallow and has a steepness that will not warrant easy movement of mine tailings down to the Markham Canyon for further disposal into the New Britain Trench. The average slope of the DSTP fallout area from the beach at Wagang village down to 700m below sea level at the Markham Canyon is only 11 degrees (24.5 %).

In the` EIS for WGM, there is a picture given that depicts the steepness of the slope from the coastline of Wagang village down to the Markham Canyon as having a slope that is almost 45 degrees in nature. However, this picture is totally misleading and is not a true representation of the DSTP fallout bathymetry. The bathymetry of the DSTP fallout, as shown in the EIS for WGM, shows clearly that the slope from the Wagang coastline down to the Markham Canyon is not so steep as depicted in the picture given.

The distance from the DSTP pipe orifice to the Markham Canyon, at 700m below sea level, is a little more than 2km. And since high density mine tailings settling at the bottom of the sea at 200m will have to be moved along a not so steep slope (11 degrees (24.5%)) against a column of water for a distance of 2km down to the Markham Canyon, how easy will that be if gravity is the major natural force?

The mouths of the Busu and Bumbu rivers are located 2km and 4km away from the DSTP pipe orifice respectively, so how easy will the forces of these two rivers contribute to the movement of mine tailings from the DSTP pipe orifice over a 2km distance down to the Markham Canyon at 700m below sea level?

Leatherback Turtle Nesting Site

One of the biggest Leatherback Turtle nesting sites in the Western Pacific and the biggest in PNG is along the Huon Coast of the Morobe Province, extending from Labu Talle village in Wampar LLG to Paiawa village in Morobe LLG. Along the Busamang and Labu Talle coastline, which is only 15km from the DSTP at Wagang village in Ahi LLG, some 200 – 300 Leatherback Turtles come on shore every year to lay eggs along a 20km stretch of beach.

The Leatherback Turtle is an endangered species according to the ICUN Red List. Therefore, the conservation of Leatherback Turtles along the Huon Coast is of paramount importance for PNG and the world at large. CEPA, as the government agency responsible for conservation in PNG, is aware of this as it is the custodian of the list of Endangered Species in PNG.

However, CEPA, the very organization that is supposed to be protecting Leatherback Turtles has now issued an EP for a DSTP to be placed in the Huon Gulf, only 15km away from where 200 – 300 Leatherback Turtles come onshore every year to lay eggs.

Annually, the DSTP is to discharge (ca.) 13 million tons of mine tailings into the Wagang coastline and ultimately into the Markham Canyon and the New Britain Trench. However, the Markham Canyon and the New Britain Trench are feeding grounds for Leatherback Turtles as these large sea creatures dive down to 1000m in search for their favourite diet of jelly fish.

The EIS for WGM, however, lacks information on Leatherback Turtles in the Huon Gulf. A little information is given on Leatherback Turtles going onshore to lay eggs along the Wagang village coastline. But information on the nesting site between Labu Talle and Busamang villages and the feeding grounds for this endangered sea creature in the Huon Gulf is lacking.

By approving an EIS and issuing an EP to WGM without giving due diligence to Leatherback Turtles and their habitat is a total disregard by CEPA for a species of high conservation status to PNG and the world.

Offshore Coral Reef Colonies and Deep Sea Fishing

The offshore area between the Markham Canyon and Salamaua Point is home to several colonies of offshore coral reefs, which are used by the people of Labu, Busamang, Buakap, Asini, Kela, Laugui and Laukanu villages for deep sea fishing since time immemorial. These colonies of offshore coral reefs have their own traditional names and the people have their own traditional GPS system to locate these reefs for fishing during the day or at night. These colonies of offshore reefs are regarded by villagers as large houses for fishes, and some educated villagers have now documented their locations using modern day GPS for deep sea fishing. The first of these offshore reef colonies, closest to the Markham Canyon, is about 12km from the DSTP fallout at Wagang.

These offshore reefs are usually at depths of 100 – 300m, and coastal villagers use them for deep sea fishing. Fish species such as Yellow Fin Tuna, Snapper species and Red Emperor are the target species, and these offshore reefs are where Salamaua villagers come to for deep sea fishing.

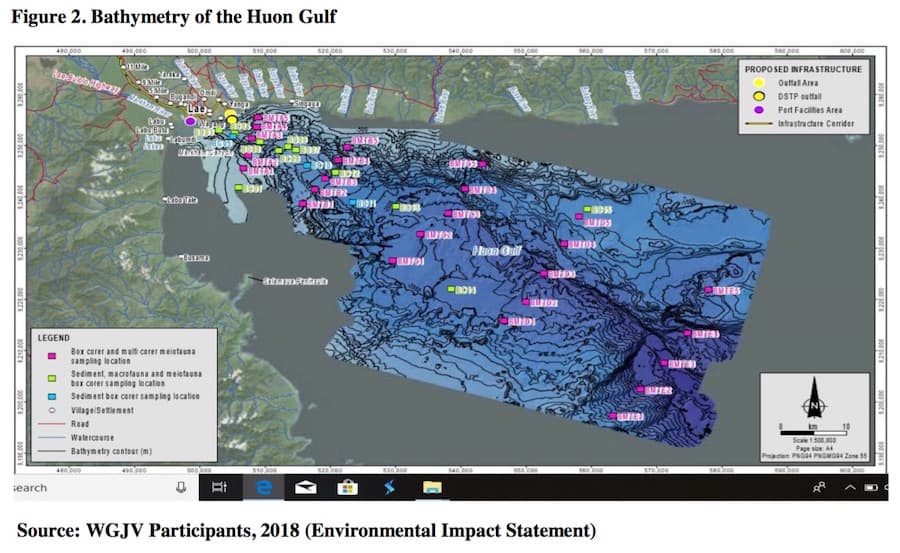

Nevertheless, the EIS for WGM lacks information on these offshore coral reef colonies. The bathymetry of the Huon Coast between Labu Talle village and Salamaua Point is not shown in the EIS because it has been blotted out (Figure 2). It is not known why the area between Labu Talle and Busamang villages all the way to Salamaua Point is not shown in the bathymetry of the Huon Gulf.

Maps produced by the National Mapping Bureau for Nassau Bay to Finsch Harbour clearly show the bathymetry of the area between Labu Talle all the way to Salamaua Point. Therefore, offshore coral reef colonies between Lae and Salamaua Point are clearly visible, and so there is no excuse for the WGM not to show the bathymetry of this area and the offshore coral reef colonies in its EIS.

Coral reefs are highly sensitive environments, and changes in ocean temperatures, pH and turbidity can easily affect these fragile ecosystems. It is already known that climate change is warming and acidifying oceans, but the sea of the Huon Gulf and coral reefs are little affected by climate change. The EIS for WGM reports that coral reef colonies extending from Busaman village to Salmaua Point are mostly in pristine conditions.

Therefore, will these offshore coral reef colonies and the fish species they house be safe from mine tailings deposited at 200m below sea level near the Wagang coastline? The answer to this question cannot be immediately answered, but time will tell because changes in ocean temperatures, pH and turbidity are time dependent issues.

Seagrass Meadows, Seaweed and Coral Reef Colonies and Climate Change Mitigation

Under the UN Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), seagrass meadows and seaweed and coral reef colonies are important components for climate change mitigation. It is scientifically known that seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows have the potential to sequester more anthropogenic carbon than forest trees, thus these carbon sinks can substantially mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change. Seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows are climate change mitigation measures under the Blue Carbon concept.

While the UNFCCC and the world is working towards coming up with innovations and consensus on how coral reefs, seagrass and sea weed are going to be incorporated into international agreements for carbon from these marine organisms to be traded on carbon markets in order to mitigate climate change, indigenous peoples have been informed and encouraged to conserve these natural resources or carbon sinks. Consequently, coral reefs, seagrass meadows and sea weed will now have important roles to play in terms of climate change mitigation and will become valuable commodities for carbon trading in the near future.

Nevertheless, the EIS for WGM lacks information on seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows along the Huon Coast. The bathymetry of the Huon Coast between Labu Talle village and Salamaua Point is not shown in the EIS, so areas that are locally known to contain seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows are not shown.

However, maps produced by the National Mapping Bureau for Nassau Bay to Finsch Harbour clearly shows the bathymetry of the area between Labu Talle and Busamang all the way to Salamaua Point. Therefore, areas where seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows are locally known to occur between Lae and Salamaua Point are clearly visible on this map, so there is no excuse for the EIS for WGM not to show the bathymetry of this area and the extent of these natural resources or carbon sinks.

The sea area between Busamang village all the way to Salamaua Point is known to contain seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows as the waters are much more crystalline compared to waters near Labu area of Wampar LLG all the way to Buhem River in Labuta LLG. The EIS for WGM also mentions that seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows in the Salamaua area are in pristine condition, but the bathymetry of this area is blotted out in the report.

Therefore, will the seaweed and coral reef colonies and seagrass meadows and the fish species they house be safe from mine tailings deposited at 200m below sea level near the Wagang coastline? The answer to this question cannot be immediately answered, but time will tell because changes in ocean temperatures, pH and turbidity are time dependent issues.

Fisheries in the Huon Gulf

Fishing is a major subsistence and income generating activity along the Huon Coast, extending from the Labu villages near Lae City all the way to the border of Morobe and Oro provinces. Busamang, Buakap, Asini, Kela, Laugui and Laukanu villages and Salamaua Station are all within the Salamaua LLG and within 30km radius of the DSTP proposed to be constructed in the Huon Gulf, and fishing is a major subsistence and income generating activity for these places.

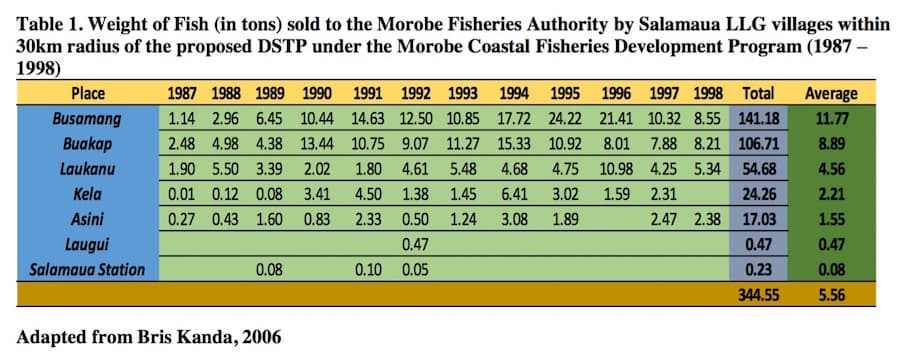

Under the Morobe Coastal Fisheries Development Program, which was implemented over a 12-year period (1987 - 1998), the total amount of fish sold by Salamaua coastal villages within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP to the Morobe Fisheries Authority was 344.55 tons (Table 1). The average amount of fish sold per village per year to the Morobe Fisheries Authority was highly variable, with Busamang village leading with an average of 11.77 tons and Salamaua Station (government station, not a village) dangles at the bottom with a mere 0.08 tons (Table 1).

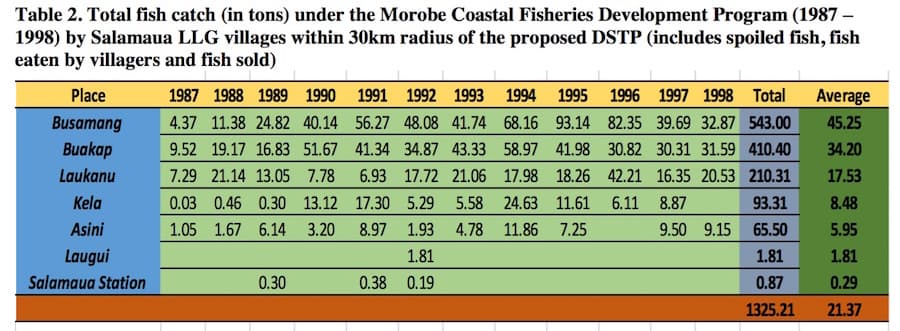

Under the Morobe Coastal Fisheries Development Program the total fish catch by Salamaua coastal villages within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP was 1325.21 tons (Table 2). The average amount of fish caught per village per year was highly variable, with Busamang village leading with 45.25 tons and Salamaua Station (government station, not a village) dangles at the bottom with a mere 0.29 tons (Table 2). According to the data collected over the 12-year period under the Morobe Coastal Fisheries Development Program, 74% of all fish caught were consumed while 26% was sold for commercial purposes and 2.5% accounted for spoilage (Bris Kanda, 2006; p.20).

The fishing catch data for coastal villages of the Wampar, Ahi and Labuta villages under the Morobe Coastal Fisheries Development Program are possibly kept by the Morobe Fisheries Authority. However, these data may be in raw form and need to tabulated for analysis. This data needs to be captured in the EIS for WGM.

Therefore, it is an enigma as to why the consultant for WGM has not obtained data from the Morobe Fisheries Authority and incorporated it into the EIS. The Morobe Fisheries Authority and the National Fisheries Authority are authorities on fisheries in PNG, so there is no excuse as to why these authorities were not consulted on fisheries data for the Huon Gulf.

The surveys carried out by WGJV consultants for deep sea and pelagic fish species in the Huon Gulf and incorporated into the EIS is flawed. Pelagic fishes like Skip Jack Tuna and Spanish Mackerel are seasonal, and they are most abundant within the Huon Gulf at certain months of the year.

Therefore, carrying out surveys for only two months of the year and concluding that the Huon Gulf lacks abundance of pelagic fish species does not stand up to scientific scrutiny and common sense. The season for pelagic fish species and locations for deep sea fishing areas within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP are common knowledge possessed by local fishermen and the Morobe Fisheries Authority, but these authorities have never been consulted.

Moreover, why didn’t the WGM consultants consult local fishermen and the Morobe Fisheries Authority to obtain background information that would have formed the basis for a genuine survey of deep sea and pelagic fishes in the Huon Gulf? If local information had been incorporated into the survey, a true data of deep sea and pelagic fish species in the Huon Gulf would have been captured and incorporated into the EIS.

The survey on deep sea fish species was carried out by WGM consultants along the Wampar, Ahi, Salamaua and Labuta coastlines. However, this survey was not carried out along the line of offshore colonies of coral reefs that extent between Lae and Salamaua Point. These colonies of offshore coral reefs are traditional deep sea fishing grounds for the Salamaua peoples, so the exclusion of these fishing grounds by the WGM consultants shows that the survey absolutely lacked scientific integrity and common sense.

Mangrove Swamps

The sea does not only end along the shoreline where people mostly swim and fish. The sea also ends at the back of mangrove swamps and saltwater marshes. These are two other areas where the high tide ends apart from the shoreline, and many benthic and some pelagic fish species use mangrove swamps for spawning and protection of their young prior to their migration into the sea.

The Labu Swamp in the Wampar LLG is one of the largest mangrove swamps in Morobe Province. The swamp extends from Labu Butu village, near the mouth of the Markham River, over a 5km distance along the coastline in the direction of Labu Talle village. The Labu Swamp is about 2km2 in area, and the mouth of the swamp is about 10km to the west of the DSTP fallout at Wagang village.

Along the Ahi and Labuta coastlines, pockets of mangrove swamps can be found starting from the eastern mouth of the Busu River in Ahi LLG area all the way to the western mouth of Buhem River in Labuta LLG area. These pockets of mangrove swamps lie within 2km – 30km from the DSTP fallout at Wagang village.

These pockets of mangrove swamps are much smaller in areas compared to the Labu Swamp, but they also provide for the sustenance and livelihoods of coastal peoples of Ahi and Labuta LLG areas. Coastal peoples use their mangrove swamps for harvesting of mud crabs, clams (kina), molluscs and fish species.

A pocket of mangrove swamp between Wagangluhu and Aluki villages within the Labuta LLG area has recently been identified as a prime habitat for saltwater crocodiles. The leather

(skin) of saltwater crocodiles is highly valued, and local peoples from the area have recently caught crocodiles from the area and sold it to the Mainland Holdings crocodile farm at 6-Mile outside Lae.

Nevertheless, the EIS for WGM contains very little information on mangrove swamps within 30km radius of the DSTP fallout at Wagang village. Although the Environment Team for WGM has been frequenting the Salamaua, Wampar, Ahi and Labuta coastlines to collect data for the EIS, mangrove swamps have been neglected even though they are integral parts of the marine ecosystem of the Huon Gulf.

Mangrove swamps are highly sensitive environments, and changes in ocean temperatures, pH and turbidity can easily affect these fragile ecosystems. The Labu Mangrove Swamp and pockets of mangrove swamps that extent along the Ahi and Labuta LLG coastlines are integral parts of the Huon Gulf, and anything that happens within the Huon Gulf will have some impact on these mangrove ecosystems.

Therefore, will the mangrove swamps and the crocodiles, mud crabs, clams (kina), molluscs and the fish species they house be safe from mine tailings deposited at 200m below sea level near the Wagang coastline? The answer to this question cannot be immediately answered, but time will tell because changes in ocean temperatures, pH and turbidity are time dependent issues.

Biodiversity within the Huon Gulf

Biodiversity conservation is an important agenda of the United Nations, for both terrestrial and marine environments. NGO groups, government agencies and donor partners are now engaging in collaborative conservation programs throughout PNG to conserve the country’s terrestrial and marine biodiversity.

The Huon Gulf is one of the largest gulfs in PNG, and covers an area of some 1500 km2. The gulf contains the Markham Canyon (underwater canyon), which terminates in the New Britain Trench, the deepest trench in PNG (reaching depths of 6000m or more). Therefore, due to the vast area of the Huon Gulf and its direct link to the deepest trench in PNG, the gulf should naturally show some high level of biodiversity.

Nevertheless, the EIS for WGM reports very low levels of biodiversity in the Huon Gulf. According to surveys carried out by WGM consultants within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP, only 8 species of fish and sharks were reported. No mention of any endangered species of vertebrates, invertebrates and flora within the area of interest were reported in the EIS.

A 2012 progressive report - BIOPAPUA Expedition: Highlighting Deep-Sea Benthic Biodiversity of Papua New Guinea – by The Museum of Natural History in France reported a high level of biodiversity within the Huon Gulf. The BIOPAPUA Expedition, which included Professor Ralph Mana of UPNG, found 2000 species of vertebrates and invertebrates in the Huon Gulf, of which 15% were new to science.

Despite the BIOPAPUA Expedition progressive report being produced in 2012, which was way before stakeholder consultations by CEPA and approval of the EIS for WGM and

issuance of an EP for operations to begin, this important scientific report was never cited in the EIS or the contents of it being used by WGM consultants in framing their biodiversity surveys in the Huon Gulf.

Professor Ralph Mana was present at the CEPA stakeholder consultations in both Lae and Port Moresby and made presentations on the BIOPAPUA Expedition and its implications for biodiversity conservation within PNG and the Huon Gulf. But despite his concerns for the impact of the proposed DSTP on biodiversity within the Huon Gulf and the lack of information on biodiversity captured in the EIS for WGM, the EIS was nonetheless approved by CEPA and a EP was issued forthwith.

Had the WGM consultants used the contents of the BIOPAPUA Expedition progressive report and others to frame their surveys, it would have given them a comprehensive biodiversity data for the Huon Gulf and identified which ones of the 2000 species to be rare or endemic within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP. Had the same report been used by WGM consultants for biodiversity surveys in the Huon Gulf, it would have facilitated identification of species of vertebrates and invertebrates that are new to science and are found within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP.

Results of the biodiversity survey done and reported in the EIS for WGM is a total contradiction to an international scientific study which included local expertise in the likes of Professor Ralph Mana. The BIOPAPUA Expedition was carried out by specialists in the different fields of marine biology, making the report scientifically genuine and reliable. But for the WGM consultants not to consult this report and other scientific studies of biodiversity within the Huon Gulf, this brings into question the integrity of the EIS for WGM, especially the biodiversity surveys carried out within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although CEPA has already approved in principal the EIS for WGM and issued a 50-year EP for operations to begin, social, economic and environment data for coastal peoples living within 30km radius of the DSTP fallout at Wagang village have not been adequately captured in the EIS.

Therefore, the EIS for WGM is not an inclusive document because the social, economic and environmental data for coastal stakeholders of the WGM have been deliberately left out. This is despite the fact that the coastal stakeholders of the mine are the very people that will dangle at the end of the chain of activities and impacts of mining that will occur inland in the Wampar and Mumeng LLG areas.

Since the current EIS for WGM has already been approved in principal by CEPA and a 50- year EP has been issued without due diligence being given to the social, economic and environmental data for coastal stakeholders, it is recommended that WGM and its consultants carry out a comprehensive study and produce a separate EIS that contains adequate social, economic and environmental data for coastal stakeholders of the mine. This must be done before the mine starts producing gold and copper.

If the developer of the WGM wants to be seen by stakeholders in its mining activities and the public as being a transparent and accountable corporate entity that lives up to good corporate responsibilities, it must carry out a comprehensive study and produce a separate EIS that contains adequate social, economic and environmental data for coastal stakeholders. Simply ignoring coastal stakeholders and their concerns for their sustenance, livelihoods and environments and refusing to develop a separate EIS for coastal stakeholders and their environments would speak otherwise of the reputation of the developer of the WGM.

We, coastal peoples of the Huon Gulf living within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP, have rights to our natural properties such as the sea, fish stocks, mangrove swamps, coral reefs, seagrass meadows and others. But since the principle of FPIC has not been used to obtain our consent for these natural properties of ours to be used or impacted in the name of WGM development, we believe our human rights have been impinged by the state and the developer.

We, coastal peoples of the Huon Gulf living within 30km radius of the proposed DSTP, have been coerced into accepting a DSTP that will affect us and our future generations (5 generations or more) through the approval in principal of the EIS and issuance of an EP to WGM by the state through CEPA.

WE NEVER GAVE OUR CONSENT FOR A DSTP TO BE CONSTRUCTED BY WGM IN THE HUON GULF.